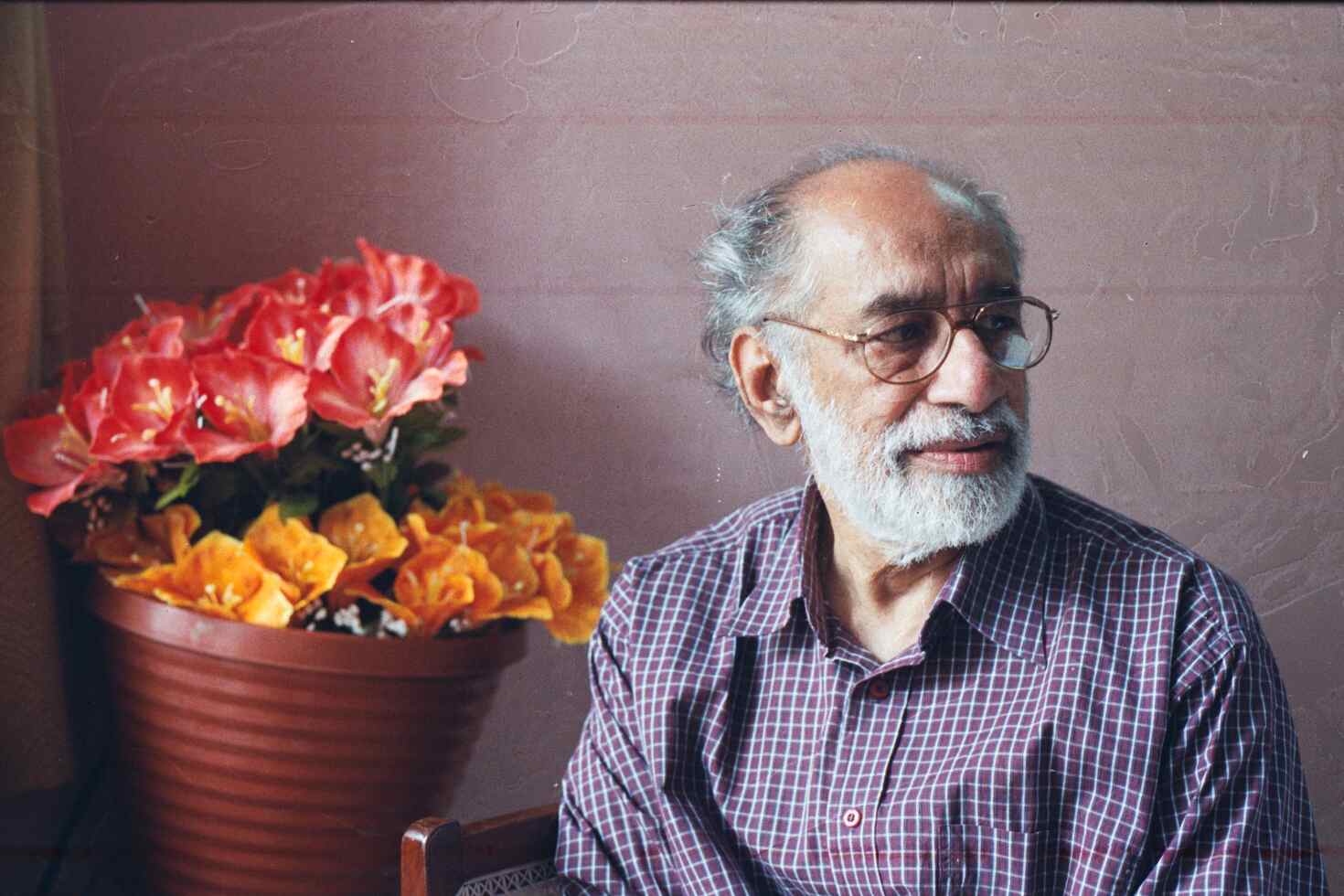

SUNDARA RAMASWAMY (1931-2005)

Sundara Ramaswamy was a renowned writer in Tamil, incomparable in his reach and versatility. His perennial interest in experimenting with forms and themes keep him within an ever-evolving act of creation. He had developed for himself a unique sense of narration, marked by a keen ear for local languages and a sense of honour. His stories make for delightful and compelling reading.

The Tamarind Tree (1966), his first novel, and J.J. Some Jottings (1981) have a cult following. All three novels of SuRa are scheduled to be issued by Penguin under its Modern Classics Series. One of our iconic writers, Ramaswamy’s stories are an ironic take on modernity’s slow ingress into traditional ways of life. He was honored for his work with the Katha Chudamani award (2004) and Lifetime Achievement award from the University of Toronto (2001).

THE TAMARIND TREE(Novel)

(OruPuliyamarathinKathai)

Number of pages: 207

Sundara Ramaswamy’s modern classic, translated from Tamil, is a simply stunning reflection about shared histories, loss, an affinity for nature, and a near-mythic centre of life in a town in India.

While it lived, the tamarind tree stood at the crossroads of a small town in southern India. For more than fifty years it was a benevolent observer, offering shade without discrimination. It bore witness to laughter and tears, to tragedy and simple pleasures, and to the history of the town itself as it transformed from the old ways of bullock-led carts to a bustling community of social, political, economic, and ecological change. And for Damodara Asan, an enigmatic philosopher, memory keeper, and master storyteller, the tamarind tree―and everything it inspired―was an endless source of tales that enthralled generations.

Unfolding through the bittersweet remembrances of an unnamed narrator who was once beguiled by Asan, ’The Tamarind Tree’ is a beautiful and universal story about transition, the compromises of progress, and a long-gone though undying symbol of indestructible dignity, culture, and life.

JJ: SOME JOTTINGS(Novel)

(J.J. SilaKurippukal)

Number of pages: 190

The undisputed classic of modern Tamil fiction, a triumph of sharp wit and scathing satire. Joseph James, or JJ, is dead. A famously outspoken figure in Malayalam literature, his death is particularly mourned by Balu, a Tamil writer who endeavors to preserve the luminary’s legacy by penning a biography of JJ. For this, Balu must immerse himself in the politicized and divisive Malayalam literary world, where JJ has made quite a few enemies. And as this enthralling novel of ideas unfolds, Balu discovers that he might have bitten off more than he can chew.

CHILDREN, WOMEN, MEN(Novel)

(Kuzhanthaigal, Pengal, Aangal)

Number of pages: 552

This ambitious novel, teeming with characters, focuses on the family of Srinivasa Aiyar or SRS, who moves from his ancestral house in Alappuzha, in Kerala, to the more modern Kottayam, before returning to Tamil Nadu, to his wife Lakshmi’s home in Nagercoil. Set in the late 1930s and reflecting the political and social turmoil of the pre-war years, it chronicles the psychological conflict between SRS and his nine-year-old son, Balu; the moral struggle of a young widow, Anandam, as she considers remarriage; and the political journey of Sridaran, who chooses to break off his studies in England in order to join nationalist activities at home.

Told from multiple perspectives, this intricately woven narrative will stand the test of time as one of the landmarks of Indian modernism.

- LAKSHMI HOLSTORM,Deccan Herald, Bangalore, 23 June 2013

Winner of the Crossword Indian language Translation award 2014.

WAVES(Short stories)

Number of pages: 200

One of the most versatile and innovative writers in modern Tamil literature, Sundara Ramaswamy wrote short stories in two phases: between 1951 and 1966, and then, after a long gap, in the 1970s. His early stories, focusing on ordinary people leading ordinary lives, are full of gems by way of characterization – the policeman Seventy-three Forty-seven and the priest of the Nadi Krishna temple in ‘Prasadam’, and Varadan and Joswin in ‘True Love’ remain unforgettable, in spite of their pedestrian lives. In the later stories – ‘Intoxication’ (1973), and ‘Waves’ (1976) – clouded by the aftermath of the Bangladesh war and the Emergency, the plots turn darker and more complex.

Surprising us with their odd twists and turns, raising uncomfortable questions, and yet touched by a fine sense of humour and humanity, the stories in this collection belong with the best in the genre.