PERUMAL MURUGAN (1966)

Born in 1966, Perumal Murugan, Principal of Anna College in Namakkal, is the author of eleven novels and five collections of short stories, poems and a memoir, as well as ten books of nonfiction. He is the Winner of ILF Samanvay Bhasha Samman 2015. His ‘One Part Woman’ and ‘The Story of a Goat’ was Long listed for the ‘National Book Awards for Translated Literature 2018 and 2020’ respectively. ‘Pyre’ was short listed for the JCB Prize and Atta Galatta – BLF award in 2018 for Translated Literature. His ‘Seasons of the Palm’ was shortlisted for the Kiriyama Prize. The International Booker-Longlisted author of ‘Pyre’. His ‘Fire Bird’ won the JCB Prize for Literature – 2023.

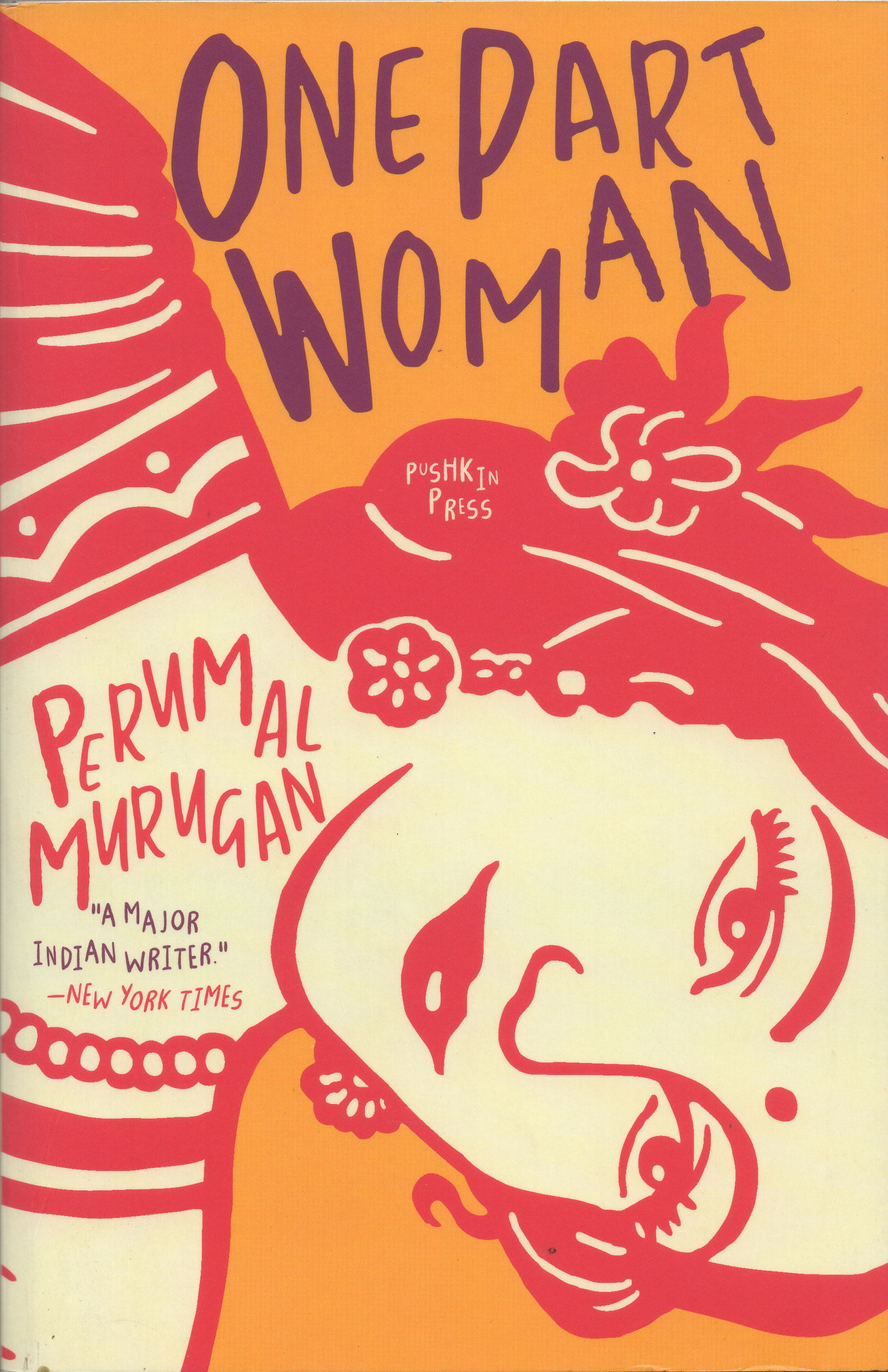

ONE PART WOMEN(Novel)

(Mathorupagan)

Number of pages: 248

Kali and Ponna’s efforts to conceive a child have been in vain. Hounded by the taunts and insinuations of others, all their hopes come to converge on the chariot festival in the temple of Ardhanareeswara, the half-female god. Everything hinges on the one night when rules are relaxed and consensual union between any man and woman is sanctioned. This night could end the couple’s suffering and humiliation. But it will also put their marriage to the ultimate test.

Long listed for the National Book Award for Translated Literature 2018.

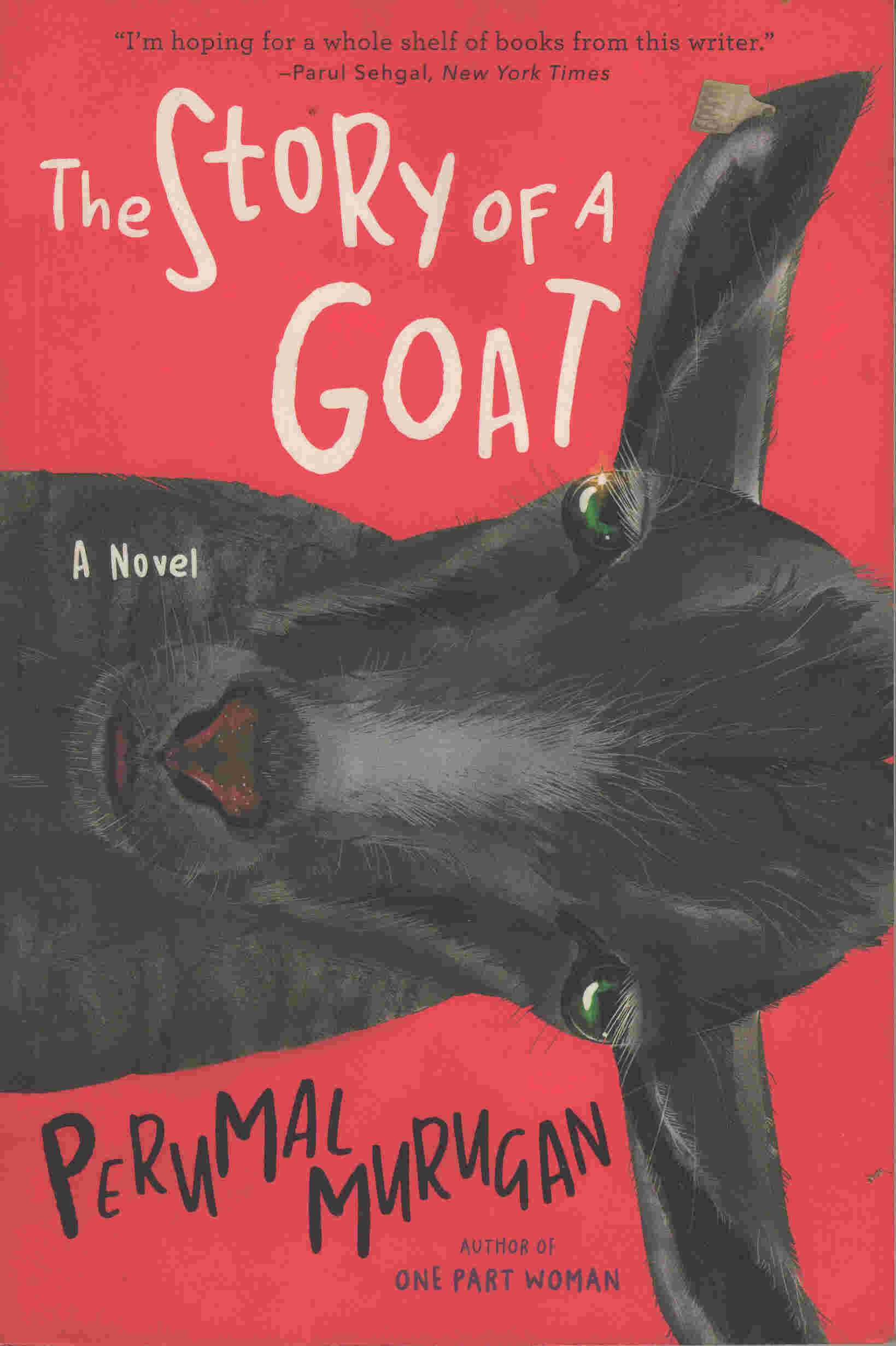

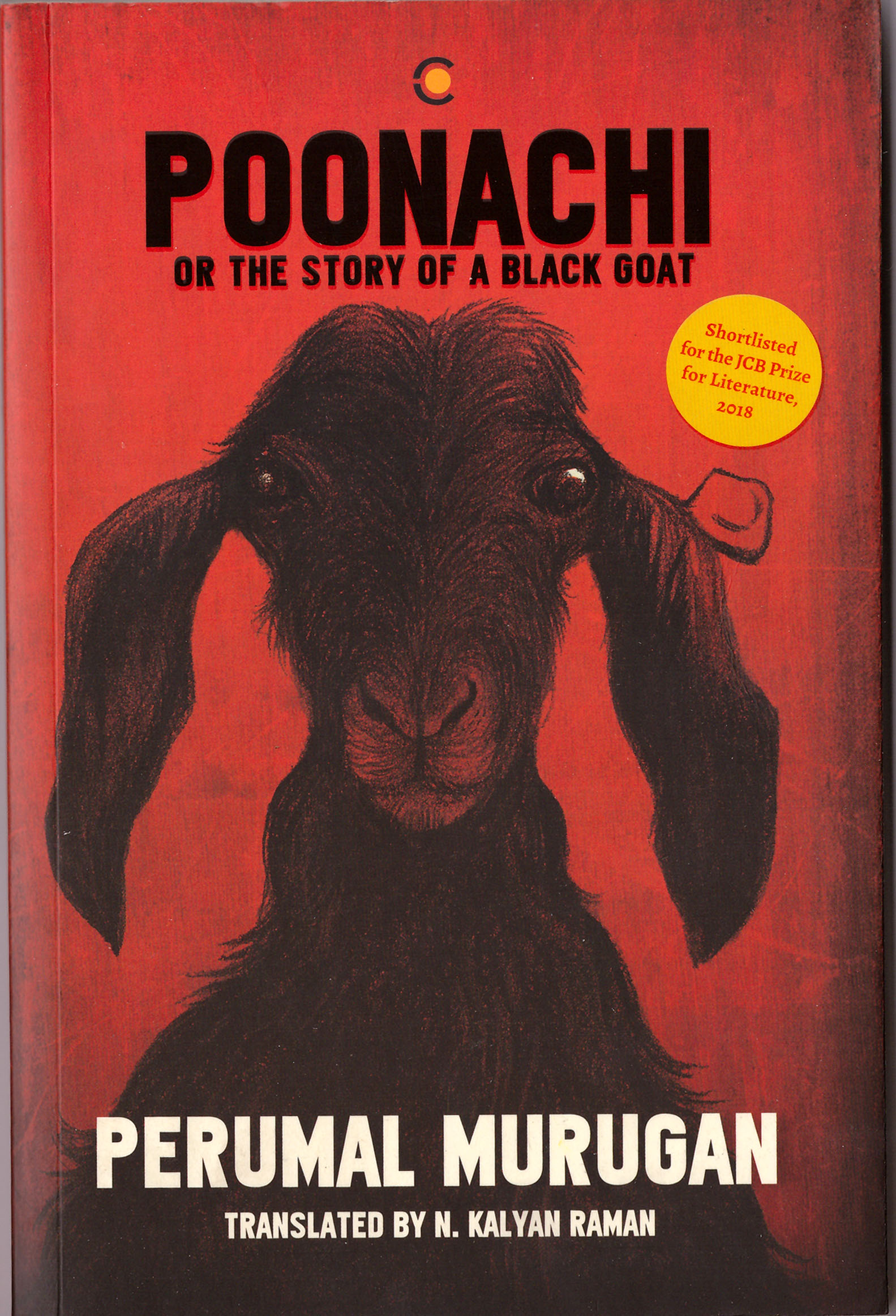

POONACHI

(PoonachiAllathuOruvellaattinKathai)

Number of pages: 174

An old man is watching the sunset over his village one quiet evening when a mysterious stranger turns up with the gift of a day-old goat kid. Thus, begins the story of Poonachi, the little black goat whose fragility and fecundity become a cause for wonderment to all those around her.

From the eagle that swoops down on her to the wildcat that attempts to snatch her away within days of her arrival, the old man and his wife struggle to keep their tiny miracle alive. Before they know it, Poonachi has become the center of their meagre world and the old woman and she are inseparable.

Life is not easy for any of them - farmers, goatherds or goats. The rains play truant, the gods claim their sacrifices, and the forest waits to lure unwary creatures into its embrace.

. Wrought by the imagination of a skillful storyteller, this delicate yet complex story of the animal world is about life and death and all that breathes in between. It is also a commentary on our times, on the unequal hierarchies of class and color, and the increasing vulnerability of individuals who choose to speak up rather than submit to the vagaries of an ambitious if incompetent state.

Short listed for the JCB Prize for Literature 2018 and AttaGalatta – BLF award in 2018

Long listed for the National Book Award for Translated Literature 2020.

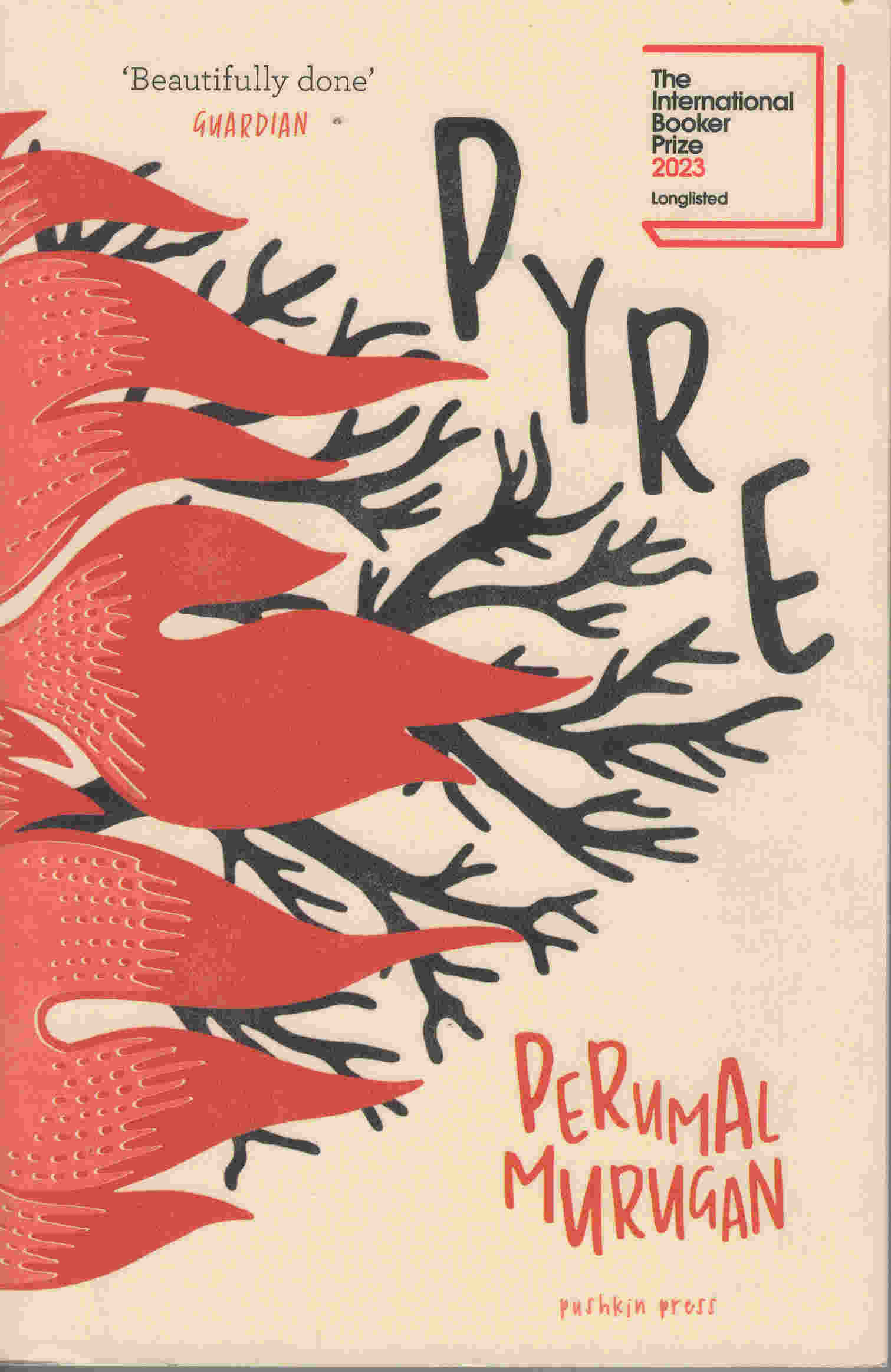

PYRE (Novel)

(Pookkuzhi)

Number of Pages: 208

Saroja and Kumaresan are in love. After a hasty wedding, they arrive in Kumaresan’s village, harbouring the dangerous secret that theirs is an inter-caste marriage, likely to anger the villagers should they learn of it. Kumaresan is confident that all will be well. He naively believes that after the initial round of curious questions, the inquiries will die down and the couple will be left alone. But nothing is further from the truth. The villagers strongly suspect that Saroja must belong to a different caste. It is only a matter of time before their suspicions harden into certainty and, outraged, they set about exacting their revenge.

With spare, powerful prose, Murugan masterfully conjures a terrifying vision of intolerance in this devastating tale of innocent young love pitted against chilling savagery.Long Listed for International Booker Prize - 2023

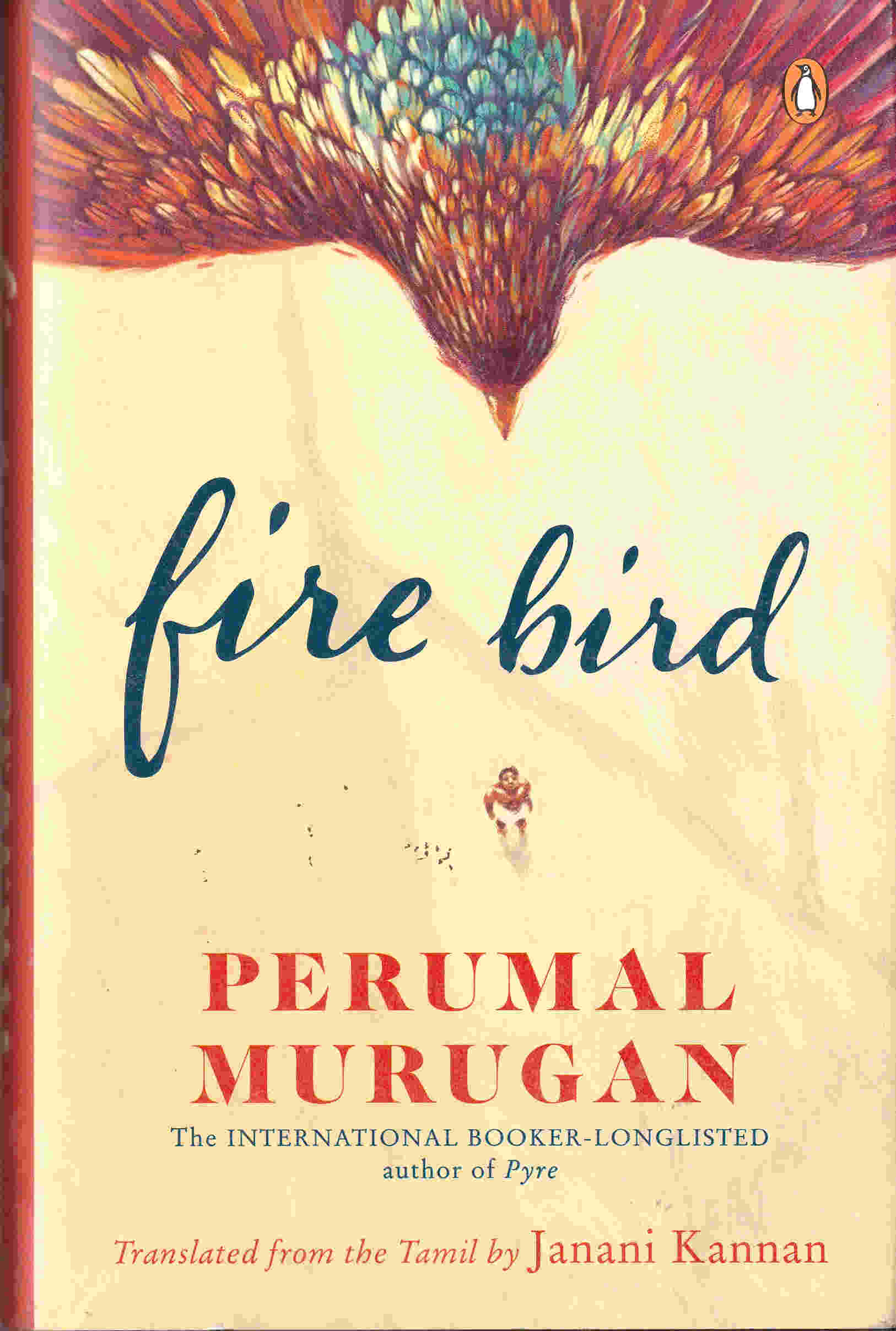

FIRE BIRD (Novel)

Aalandapatchi

Number of Pages : 294

Fire Bird is a masterfully crafted tale of one man’s search for the elusive concept of permanence. Muthu has his world turned upside down when his father divides the family land, leaving him with practically nothing and causing irreparable damage to his family’s bonds. Through the unscrupulous actions of his once-revered eldest brother, Muthu is forced to leave his supposedly perfect world behind and seek out a new life for himself, his wife and his children.

In this transcendental novel, Perumal Murugan draws from his life experiences of displacement and movement, and explores the fragility of our fundamental attraction to permanence and our ultimately futile efforts to attain it. Translated from the nearly untranslatable ‘Aalandapatchi’, which alludes to a mystical bird in Tamil, the titular fire bird perfectly encapsulates the illusory and migratory nature of this pursuit.

Fire Bird is a thought-provoking and beautifully written exploration of the human desire for stability in and ever-changing world.

This Novel won The JCB Prize for Literature – 2023.

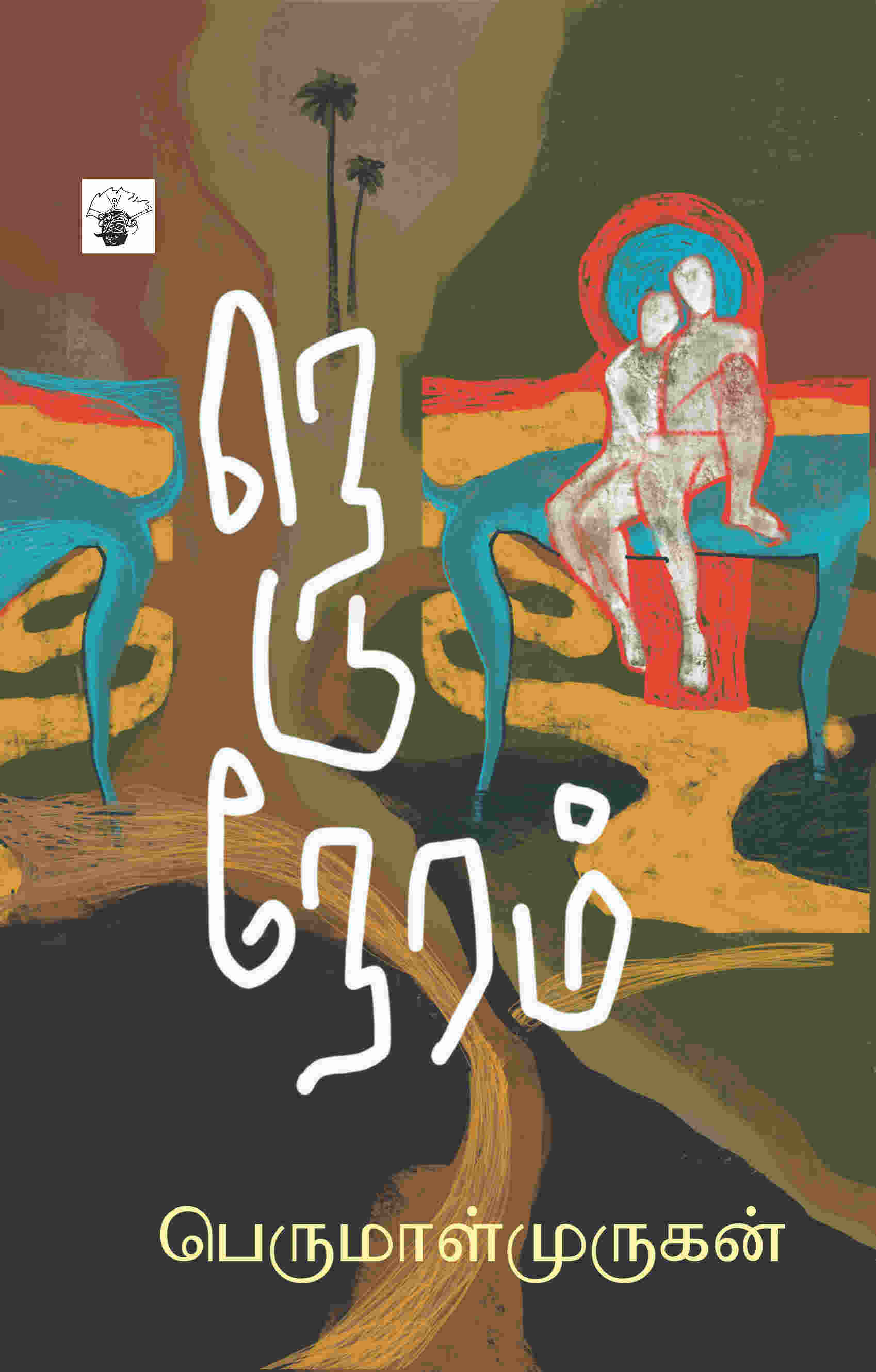

NEDUNERAM (Novel)

Number of Words in Tamil : 63,209

Perumal Murugan’s novel ‘Neduneram’ (A Long Time) does not fall into any genre that the author is known for. It is a love story, or a story of several loves intertwined with each other, that reveal and rediscover each other at opportune and some inopportune moments.

The novel starts with a startlingly nonchalant revelation. Mangasuri, married to Kumarasuran for four decades, and who has had three children with him, goes missing. Kumarasuran manages his life without her, without revealing to any of his children until Murugasu comes home one day to discover the fact, almost a year later thanks to the Covid lockdown.

It is their son, Murugasu, who stumbles upon this concealed truth, and driven by his determination, he embarks on a mission to find his mother. Accompanied by his steadfast friend, Megasu, he embarks on a journey that uncovers not only the whereabouts of Mangasuri but also a slew of family secrets - from a harrowing tale of his grandparents’ tragic end to his parents’ marriage, which was forged under duress.

The novel navigates the complexities of love, both lost and found, with remarkable sensitivity. It places a significant emphasis on the themes of family acceptance and understanding, portraying how love can resurface in the most unexpected ways.

What sets ‘Neduneram’ apart is its treatment of Mangasuri’s character, whom the reader never directly encounters. Instead, her character is meticulously crafted through the perspectives of those around her, offering a unique and compelling window into her life. Mangasuri’s story is one of profound courage and the pursuit of personal fulfillment, as she chooses to live life on her own terms after dutifully fulfilling her roles as a wife and mother.

In this sense, ‘Neduneram’ is not only a literary gem but also a rare and powerful portrayal of a woman’s agency in Tamil literature and society. Perumal Murugan’s masterful storytelling, combined with the depth of character exploration and the intricacies of love and relationships, make ‘Neduneram’ an unforgettable and thought-provoking reading experience.

VEL

Number of words in Tamil: 33387

In a marked departure from his usual themes, acclaimed writer Perumal Murugan explores new territory with Vel, a collection of short stories that delves into the evolving role of pets in Indian households.

While his previous works have often featured animals in the context of agrarian life, Vel explores how pets, especially cats and dogs, have become integral to both rural and urban homes in recent years. Murugan’s narratives shed light on how the presence of pets in households has transformed daily routines and impacted the emotional landscape of families. The rise of nuclear family structures, the migration of children for education and employment, and the increasing isolation of older generations have left many grappling with feelings of loneliness. In this context, the companionship of pets has emerged as a source of comfort. In both urban and rural environments, pets have evolved from mere sources of entertainment or security to vital emotional anchors, providing solace and a sense of routine.

At the core of Vel is the author’s examination of how pets transform human relationships. These changes can be humorous, as animals seem to adopt human-like qualities, and at times deeply moving, as pets serve as substitutes for human companionship. Murugan contemplates the expansion of the human-pet relationship, suggesting that while connections between people may fade, the presence of pets remains a steadfast source of comfort.

NOVELS

TRAIL BY SILENCE

(Arthanaari)

Number of pages: 248

At the end of Perumal Murugan’s trailblazing novel One Part Woman, readers are left on a cliffhanger as Kali and Ponna’s intense love for each other is torn to shreds. What is going to happen next to this beloved couple?

In Trial by Silence-one of the two inventive sequels that picks up the story right where One Part Woman ends-Kali is determined to punish Ponna for what he believes in an absolute betrayal. But Ponna is equally upset at being forced to atone for something that was not her fault. In the wake of the temple festival, both must now confront harsh new uncertainties in their once idyllic life together.

In Murugan’s magical hands, this story reaches a surprising and dramatic conclusion.

‘The most accomplished of his generation of Tamil writers’ - Caravan.

‘[An] extraordinary writer’ - The Hindu

Short listed for THE JCB PRIZE LITERATURE – 2019

A LONELY HARVEST

(Aalavaayan)

Number of pages: 250

At the end of Perumal Murugan’s trailblazing novel One Part Woman, readers are left on a cliffhanger as Kali and Ponna’s intense love for each other is torn to shreds. What is going to happen next to this beloved couple?

In A Lonely Harvest-one of two inventive sequels that pick up the story right where One Part Woman ends-Ponna returns from the temple festival to find that Kali has killed himself in despair. Devastated that he would punish her so cruelly, but constantly haunted by memories of the happiness she once shared with Kali, Ponna must now learn to face the world alone.

With poignancy and compassion, Murugan weaves a powerful tale of female solidarity and second chances.

‘The most accomplished of his generation of Tamil writers’ - Caravan.

‘[An] extraordinary writer’ - The Hindu.

SEASONS OF THE PALM

(Koolamaathari)

Number of Pages: 332

Shortly, a young untouchable farmhand, is in bondage to a paternal yet powerful landlord. He spends his days herding sheep and tilling the fields, caught between the rigours of an unforgiving life and the solace he finds in nature and the company of his friends. He struggles to keep a fragile happiness, but endless work and a stubborn hunger gnaw away at his spirited innocence. And before long, shortly must confront the unyielding reality of his situation.

Poignant and powerful, Seasons of the Palm is lyrical in its evocation of the grace with which the oppressed come to terms with their dark fate.

‘A powerful novel . . . [Murugan] recounts the everyday brutality of caste society in relentless detail’ – The Hindu

Shortlisted for the Kiriyama Award (2005 fiction finalist).

CURRENT SHOW

(Nizhal Muttram)

Number of Pages: 186

Set in a small highway town in South India, Current Show revolves around Sathi, a young soda-seller in a run-down theatre. This is life lived on the margins of the film world, far beyond glitz and glitter of Tamil cinema.

Ill-paid and always tired, Sathi finds relief from the tedium of the everyday in marijuana. His company of friends is all vulnerable, desperate young men, who work around the theatre and alternately bully and support each other. An intense and tender friendship with one of the men sustains Sathi, until a train of events throw his days and nights into disarray.

ESTUARY

(Kazhimugam)

Number of pages: 244

On answering the phone, Meghas would say, ‘Solluppa’-tell me, Appa-his only world through the entire call. On some days, he said it fast; on others, he said it gently; on still others, he barked it out; and there were days when he seemed to speak it with hate and resentment. A single word could be a storehouse of emotions, each utterance stirring a different one. It could unleash a torrent, a flash flood, a stream, a wave. Kumarasurar would instantly guess Meghas’s mood from his intonation and fortify himself to counter it.

RISING HEAT

(Eru Veyyil)

Number of pages: 230

‘Versatile, sensitive to history and conscious of his responsibilities as a writer, Murugan is […] the most accomplished of his generation of Tamil writers’ - CARAVAN

‘His fiction scrupulously documents South India’s trees, its seasons, the behaviour not only of people but even of animals’ - NEW YORKER

‘Murugan works his themes with a light hand; they always emanate from his characters, who are endowed with enough contradiction and mystery to keep from devolving into mouthpieces […] I’m hoping for a whole shelf of books from this writer’ - NEW YORK TIMES

RESOLVE

(Kanganam)

Number of pages: 396

It might be a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good forutune, or at least a piece of land, must be in want of a wife, by Marimuthu’s path to marriage is strewn with obstacles big and small. Inward-looking, painfully awkward, desperately lonely and deeply earnest, Marimuthu is fuelled by constant rejection into an unforgettable and transformative matrimonial quest. Enter a series of marriage brokers, horoscopes, infatuations, refusals and ‘bride-seeing’ expeditions gone awry, which lead Marimuthu to a constant re-evaluation of his marital prospects.

But this is no comedy of manners, and before long we find ourselves reckoning with questions of agricultural change, hierarchies of caste, the values of older generations and the grim antecedents of Marimuthu’s poor prospects, as decades of sex-selective abortion have destroyed the fabric of his community and its demographics.

Perumal Murugan’s Resolve is both a cultural critique and a personal journey: in his hands, the question of marriage turns into a social contract, deeply impacted by the ripple effects of partriarchy, inequality and changing relationships to land and community. In this deceptively comic tale that savagely pierces the very heart of the matter, translated with deft moments of lightness and pathos by Aniruddhan Vasudevan, Perumal Murugan has given us a novel for the ages.

‘Murugan works his themes with a light hand; they always emanate from his characters, who are endowed with enough contradiction and mystery to keep from devolving into mouthpieces’ – New York Times

‘Murugan’s unsurpassed ability to capture Tamil speech lays bare the complec organism of the society he adeptly portrays.’ – Guardian

‘Versatile, sensitive to history and conscious of his responsibilities as a writer, Murugan is […] the most accomplished of his generation of Tamil writers.’ – Caravan

‘[Murugan’s] fiction scrupulously documents South India’s trees, its seasons, the begaviour not only of people but even of animals.’ – New Yorker

SHORT STORIES

THE GOAT THIEF

(Perumal Murugan selected his best stories)

Number of Pages: 208

Perumal Murugan is one of the best Indian writers today. He trains his unsentimental eye on men and women who live in the margins of our society. He tells their stories with deep sympathy and calm clarity. A lonely night watchman falls in love with the ghost of a rape victim. A terrified young goat thief finds himself surrounded by a mob baying for his blood. An old peasant exhausted by a lifetime of labour is consumed by jealousy and driven to an act of total destruction. Set in the arid Kongu landscape of rural Tamil Nadu, these tales illuminate the extraordinary acts that make up everyday lives.

FOUR STROKES OF LUCK

(Perumal murugan selected short stories)

Number of Pages: 216

Amma is unable to live without Seematti, her beloved buffalo. Kumaresu has found success in business, but he has never been able to overcome rejection by his childhood sweetheart. Every day, Murugesu hides in a neem thicket, where he extorts money from young couples. Mocked all her life for her dark skin, Saraswati is kept going by her burning private passion for a movie star.

From one of India’s most acclaimed and beloved modern writers. Four Strokes of Luck is a collection that will delight every admirer of Perumal Murugan, and introduce new readers to his hallmark empathy, humanity and humour. These stories of lives on the margins, of loners and outcasts seeking meaning and happiness, are tender, heartbreaking and always surprising.

‘The most accomplished Tamil writer of generation.’ – Caravan

‘Murugan’s unsurpassed ability to capture Tamil speech lays bare the complex organism of society he adeptly portrays.’ – Meena Kandasamy, Guardian.

‘Murugan’s willingness to look into the dark well of prejudice and see his society’s face reflected there . . . [gives] his writing its power.’ ‘Here is a hero we need . . . Perumal Murugan’s short stories hold the depth of his novels but with and added touch of lightness.’ – scroll.in

SANDAL WOOD SOAP and Other stories

(Perumal murugan selected short stories)

Number of Pages: 202

MEMOIRS

AMMA

(Essays of Memoirs)

(Thondra Thunai)

Number of Pages: 192

Perumal Murugan’s tender yet truthful essays capture the life of a strong, independent and extraordinary woman: his mother. She raised her children with the income from just a few acres of land that she managed on her own, tending to the cattle and crops with maternal concern, all the while minding her unruly husband. Every obligation met, all accounts squared up, each meal cooked to satiate the tongue and heart-Amma never rested, not even when bedridden with Parkinson’s. She lived a farmer’s life and died a farmer’s death.

Amma is ahomage to way of life and values-simplicity, honesty and hard work-lost to us today. Peppered with undentimental nostalgia and delightful humour, and vividly documenting village and farming life in the Kongu region, Amma tugs at generational memory. Murugan’s non-fiction writing, his first to appear in English, is as deeply affecting as his fiction

POEM

SONGS OF A COWARD

(Kozhaiyin Paadalgal)

Number of Pages: 292

A haunting and luminous collection of poems by one of India’s most incandescent writers.

A king decrees that all humans be skinned alive. A man runs from words that hound him like a pack of wolves. A legion of white snakes sweeps across a land blighted by drought. A beleaguered soul laments the loss of a homeland.

By turns passionate, elegiac, angry, tender, nightmarish and courageous, the poems in Songs of a Coward weave an exquisite tapestry of rich images and turbulent emotions. Written during a period of immense personal turmoil. These verses, an enduring testament to the resilience of an imagination under siege, show how poetry came to Murugan’s rescue in his darkest moments.

This edition also includes ‘Growing Out of the Cocoon’, Murugan’s powerful and moving statement, delivered in 2016, announcing his return to writing and describing the profound impact of poetry on his life.

EDITED BOOK

BLACK COFFEE IN A COCONUT SHELL

(Essays)

(Saathiyum Nanum)

Number of Pages: 230

Perumal Murugan’s Works have been Translated into Several Global Languages.

Pyre - US & UK

Pyre - FRENCH

One Part Women - TURKEY

One Part Women -GERMAN

One Part Women - UK & US

One Part Women - CZECH

One Part Women - SLOVENIA

The Story of a Goat - TURKEY

The Story of a Goat - ITALY

The Story of a Black Goat - CHINA